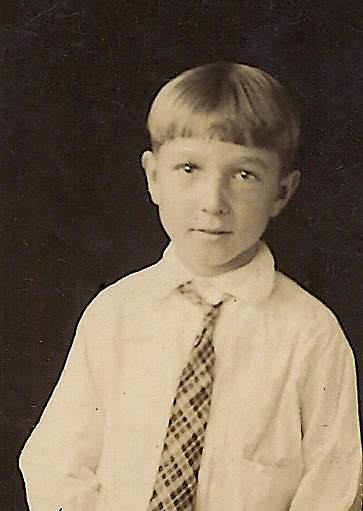

My dad was born 100 years ago, today, on September 29, 1920.

My grandparents thought it fortuitous—their first son born on the feast day of St. Michael the Archangel, for whom my dad was named.

Michal grew up in a turbulent era, but in the environment of a problem-solving family. Paired with the occasional prompting by his parents and others about the significance of his naming, he became a strong, wise, and multi-skilled man who was a good son, brother, husband, and father.

On his birthday, Mom often prepared his favorite dessert: apple pie. Lucky for him, Mom’s apple pie was exceptional.

So, this week we’ve been eating homemade apple pie in honor of Dad. In addition, I’m posting a piece I wrote in early 2020.

Dreaming of Dad’s Workshop

When I needed a rest during the house clean-out, I sat on the same lower steps of the basement staircase where, as children, my two sisters and I had watched Dad work on whatever project was fascinating him at that moment.

We could easily sit for an hour on those steps, the spot Dad designated to keep us safe from flying wood chips and plumes of sawdust.

Forever patient, he welcomed our questions while he worked. My sisters and I appreciated his simple, clear explanations, but equally, that Dad didn’t really treat us like kids. These were a few of the reasons he became as beloved to us as his grandfather had been to him.

It would be other people who noticed Dad’s rare ability to explain something complicated in a few sentences.

Perhaps he acquired this talent while instructing apprentice carpenters at the construction sites where he spent his working life. That seems the case for a classmate of mine. At one of my high school reunions, he emoted how grateful he was to have learned carpentry from my dad, who he described as a generous and highly skilled man.

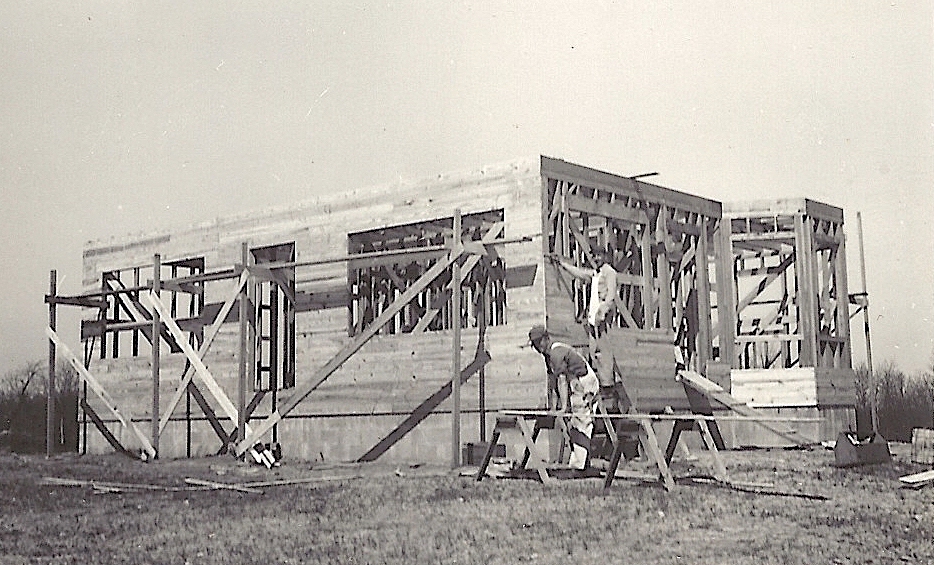

My uncle and I talk sometimes about their 1947-1950 two-house construction project, accomplished while Dad was an apprentice carpenter and both held full time jobs. In those years, Uncle Tony bought an electric saw for my father, a gift. My uncle, three years younger than my father, has joked with a twinkle in his eye that he was my father’s “assistant” while they built their two houses, a role he filled often during their younger years. My uncle didn’t seem to mind at all being the kid brother. When I’ve asked him and my aunts what Dad was like growing up, they have commented that Dad was a good brother: helpful, reliable, caring, and protective. Over time, I have come to realize the four shared these traits.

The electric saw held the center spot in Dad’s workshop. It sat like an island on the cement floor, giving him plenty of room to maneuver long lengths of lumber. Nearby, in the northeast corner of his space, Dad installed a long, raised work table (on the east wall) and storage drawers (against the north wall).

Sometimes we stood side-by-side with him as Dad worked on things, and we asked our questions. Of course, whenever he used his saw, we were settled 10-12 feet away on our step—blocking our ears and closing our eyes as Dad guided a piece of lumber into the saw blade, its grinding and squealing propelling the sweet aroma of fresh sawdust.

We’d see him draw another piece of lumber, often from the stacks a few feet in front of us. Dad had rigged the basement support poles and ceiling joists to hold lengths of lumber, tubing, and other useful supplies.

Over time, Dad’s space expanded. He loved discovering and collecting all kinds of bargain treasures—usually finding them in area junkyards and yard sales, as well as the discard piles at construction sites.

I remember how pleased he was to buy a bunch of metal bureaus.

The row of them became a fixture along the west wall in our former play area across from the basement stairs. They filled with metal, plumbing and auto parts, our childhood games and puzzles, and other items from his collection activities.

When Dad was “puttering around” in his workshop, the light in the space seemed brighter, as if the sun was shining in that side of the cellar where Dad made his magic. My memory of it is not unlike this photo of Mom’s kitchen, located above his workshop. The kitchen workspace glowed with a similar personality, because it faced east as well.

The little car he built for us, a neighborhood sensation in the early 1960s, took shape in Dad’s mind when he found four small wheels at the junkyard.

The little car he built for us, a neighborhood sensation in the early 1960s, took shape in Dad’s mind when he found four small wheels at the junkyard.

He built a prototype first. Its engine and mechanicals were open to view. After he had smoothed out its workings, Dad took it apart and started over.

The result: 0ur aqua mini Chevy Corvair—a two-seater with engine in the rear, fiberglass–covered metal frame, steering wheel, gas pedal, and brakes.

While my sisters and I were growing up, Dad’s electric saw got lots of use, for construction projects at our house or someone else’s. Rarely short of energy, Dad spent significant blocks of his spare time devoted to projects involving wood and other materials, often for relatives.

Throughout his life, he thrived on creating things and learning how things worked. He helped me understand that good design can be found at all prices, and created by people of all ages and experience. My dad helped my sisters and our cousins to believe we could do anything, if we “put our minds” to it, as he would say. Dad’s positive influence, especially in this aspect, was possibly greater than we comprehend. Just one example… One of my cousins, who adored my dad, often exclaimed with pride that his Uncle Mike was an inventor. That cousin, of modest means initially, became an engineer and patent attorney who spent much of his career at the U.S. Patent Office.

Yes, Dad so loved experimenting and creating things… And we loved that about him.

One spring, it was kite design. He would wet and shape the narrow wood dowel rods into frames which he covered with a lightweight plastic, and then add a tail of rag pieces knotted together. When he thought the newest variation was ready for trial and the wind was right, we’d head outside with him to the field behind our house. One of us would run with it, gradually releasing the string cord attached to the newest diamond, box, or teardrop kite. Would it fly? How long? Many crashed into the ground. Dad would laugh, or shake his head with a smile, and so would we. His few words of commentary would be something like, “I think I know what we’ll try next.”

Our young years in the constant bright light of Dad’s imagination and skill prepared us well for our respective futures. In what seemed a series of quick blinks from our childhood to graduations to planning our parents’ 50thwedding anniversary celebration, my sisters and I found ourselves preparing to let go of this house our father and his brother built with their own hands, as well as its acreage of family land acquired by our grandparents in the 1920s.

Our young years in the constant bright light of Dad’s imagination and skill prepared us well for our respective futures. In what seemed a series of quick blinks from our childhood to graduations to planning our parents’ 50thwedding anniversary celebration, my sisters and I found ourselves preparing to let go of this house our father and his brother built with their own hands, as well as its acreage of family land acquired by our grandparents in the 1920s.

Our “Greatest Generation” parents maintained their house and kept their modest possessions in good working order. Once the difficult decision was made to sell our family home, my two sisters and I agreed on which property elements needed sprucing up and then figured out the what, why, how, when, and who project planning details, as well as the clean-out tasks.

My youngest sister, my husband, and I teamed up to clean out the basement, shed, and yard. The basement had been Dad’s territory; the first and second floors belonged to Mom. Dad owned many fine tools and saw the practical potential in the items he collected over the years. He rarely discarded anything.

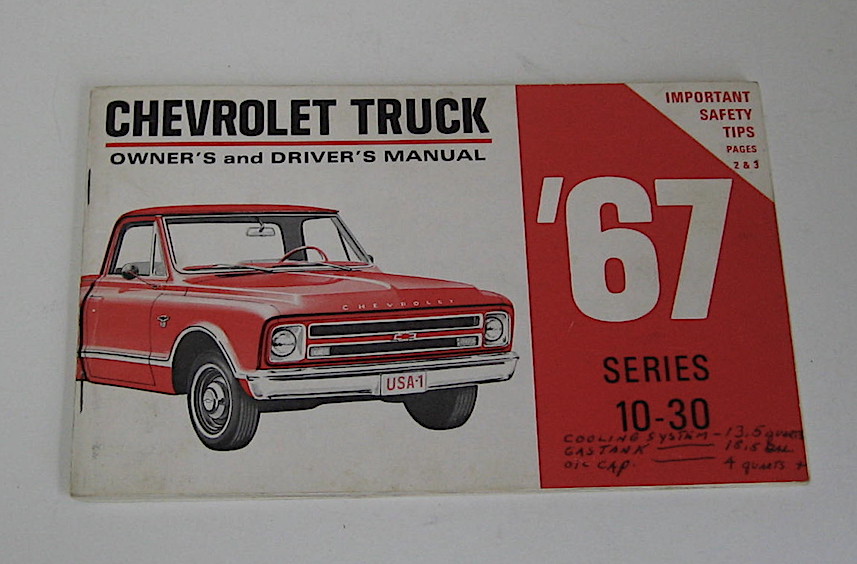

For example, we found the repair manuals of every car and truck our parents had owned.

Dad would have been thrilled that vintage car enthusiasts bought many of these, as well as car showroom brochures from the late 1960s.

So many basement clean-out items triggered nostalgic memory sharing, but a pervasive sadness settled in between the physical tasks. Tears welled up again and again, but we tried to remember Dad’s advice. A United States Marine during World War II, Dad taught his three daughters that in any taxing or critical situation we would be better able to think clearly if we could control our emotions.

That may explain why my two sisters and I rarely stepped into Dad’s workshop after he died. By the time we were cleaning out the basement, the space seemed dark and dingy, and so devoid of energy, even with lights at full blast. At times I worried I was throwing away things he valued. We were able to sell a good portion of Dad’s metal, wood, and other treasures, a somewhat consoling achievement in his honor, and consistent with his and Mom’s values.

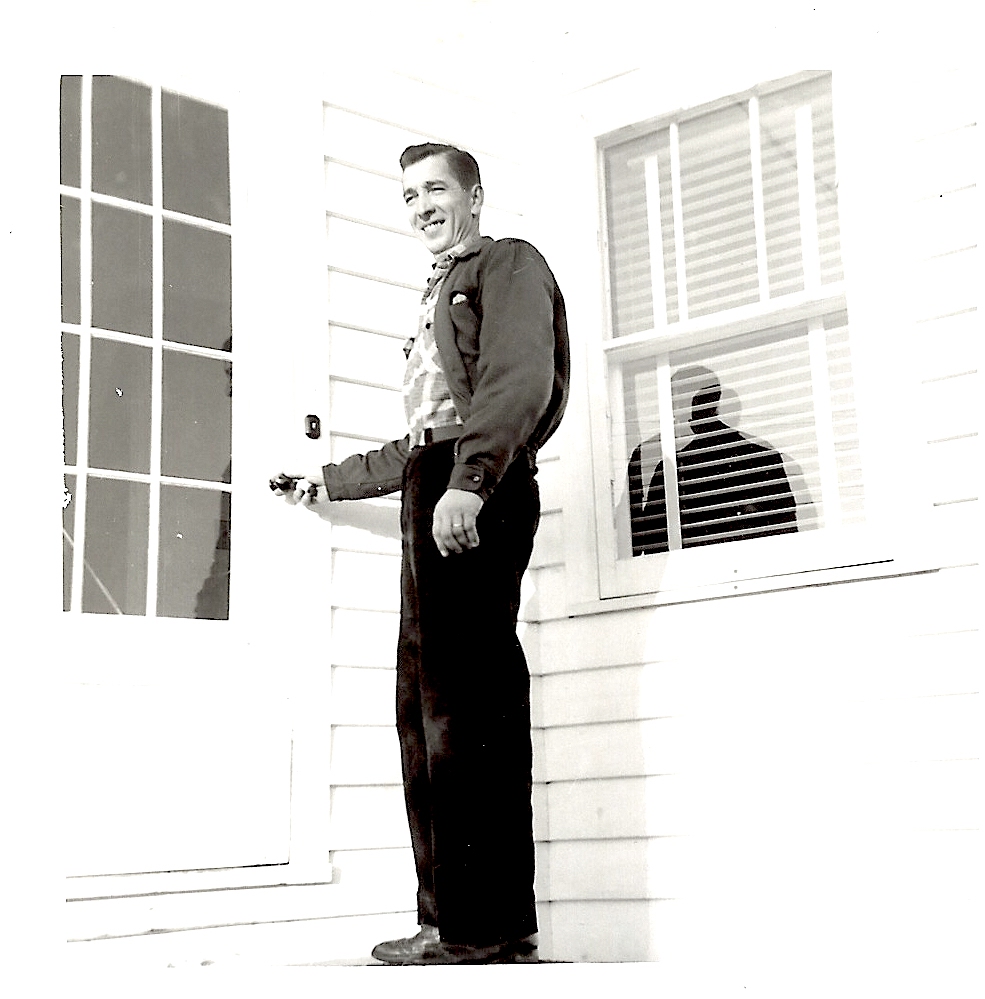

I think my parents hoped one of their daughters, a grandchild, or a cousin might take over the house. So, I wasn’t surprised by a dream one night in a period between listing agents, in which a youthful version of my dad, visible in the window of the side door, beckoned me with his arm.

I think my parents hoped one of their daughters, a grandchild, or a cousin might take over the house. So, I wasn’t surprised by a dream one night in a period between listing agents, in which a youthful version of my dad, visible in the window of the side door, beckoned me with his arm.

Was he inviting me to return home to live? A few nights later, his subtle pitch was stressing me. Before falling asleep, I pleaded, “Dad, can’t you help us find a nice couple for your house?”

Within two weeks, in a difficult buyer’s market (the first contract had broken), a new contract was signed and the closing followed as scheduled. After a year of preparing our parent’s home for sale, three listing agents, and months of showings, a nice young couple bought the property.

She was excited about the quantity of storage compartments Dad built into every nook of the second-floor eaves. He immediately set up his tools in the skeleton of Dad’s old workshop. (Note: This is the angle of the view from near the basement stairs where we sat watching our dad. His electric saw was positioned between the two parallel red lines in the photo, lower right.)

A few months later, my youngest sister and I discovered we were toiling in the same recurring dream. Actually, she and I had experienced identical recurring dreams in past years—one about searching without success for a clean toilet in unfamiliar buildings and another about wandering through our nearly empty childhood home, its rooms littered with packing boxes.

In our newest identical recurring dream, the real estate closing has not occurred yet. In our separate dreams, I find myself in the basement alone and she finds herself in the basement alone—scurrying around to remove things, but knowing the looming deadline will not be met. She and I wondered why both of us were stuck alone in this scene and situation that did not happen. Neither of us had an answer.

A low-grade heartache lingered for me after the house clean-out, the closing, and the return to “normal” life. One day, I realized I had not let go of our family home. Not really. I still wished we could have kept the house in the family. I still regretted every minute of dismantling Dad’s favorite spot in the world.

In my dreams that night, I found myself back in Dad’s workshop in half-light. As I looked upward, a blurry face appeared in the joist space. I wasn’t certain who this was, until I heard his voice say my name. This was the only time Dad ever spoke to me in a dream.

I admitted the regrets to him—the regrets I’d acknowledged to myself before falling asleep. Dad gazed at me, and then in his classic brevity and gentle voice said, “Please don’t worry about this…. It wasn’t meant to be.”

© 2020, Bernice L. Rocque. All rights reserved.

My personal thanks to my sister Cindy for providing a photo of our dad’s electric saw.

Oh how I loved reading this. Most of us have been in the same emotional place. It is heart breaking when we have to let go of a childhood home. No matter in what area of the country we find ourselves, the similarities are there.

Thanks for your thoughts, Judith. I agree it is a universal loss which many of us experience.